I have been an avid drum and bass fan since about 2012, and in 2014 I started creating my own DJ mixes as a hobby. Like many other fans of electronic music, I greatly enjoy listening to DJ mixes: the masterful way in which DJs blend individual songs together turns the listening experience into a magnificent and intriguing journey.

When I was offered the opportunity to do my master’s thesis on creating an automated DJ system, I didn’t hesitate a second and jumped right onto it! It has been a project that allowed me to combine my passion for music and computer science, and even after I finished my master’s thesis I continued work on this project during the summer of 2017. This effort has culminated in a system that works surprisingly well: it can create nice, seamless and enjoyable DJ mixes, starting from the raw audio files (so no pre-made annotations, except for those it made itself!).

This blog post gives a high level overview of how the automatic DJ system prototype works, how its different components are implemented and how they cooperate to create seamless DJ mixes, much like how a professional DJ would do that. First, there’s a quick crash course into DJing and drum and bass music. Then follows a discussion on how the automatic DJ system discovers the hierarchical musical structure of the music. Finally, I explain how the auto-DJ selects the songs it wants to play, determines their timing, and performs the actual mixing. For a more technical description, I refer to my master’s thesis1, or to the paper I wrote on the extended version of this prototype2 (link TBA as it is currently under review).

Here you have some examples of what the end result sounds like; you can listen to it while reading the remainder of this blog :)

Mix 1:

Mix 2:

Introduction: What is a DJ?

Let’s start with the basics and ask ourselves: what is a DJ? Not in a philosophical sense or anything, but more from an engineering perspective: what tasks does a DJ need to perform in order to create a good mix?

First of all, a DJ needs to know the music structure. DJing is all about joining songs together in a seamless way to create a nice and fluent mix. This means that the DJ can’t just start playing the next song whenever he wants to: he needs to carefully choose the cue points, i.e. the time instants in the songs where to start playing them, and wait until the right moment to start a transition between songs. This is because music is a very structured audio signal that is built up in a hierarchical way (more on that later), and that structure needs to be respected during the DJ set: the DJ needs to properly align the beats of the music (known as beatmatching) and to align the higher-level musical “segments” (known as phrasing). Otherwise, the resulting mix sounds very cluttered and chaotic.

Secondly, the DJ needs to know his music library. This means that he needs to know what songs fit together and which ones don’t, what music gives rise to which emotions, what he should play to excite the crowd and what he should play to make them relax. This knowledge is incredibly important to create a good tracklist, the list of songs the DJ plays during his set. Typically, the DJ ensures that there is some kind of progression throughout the DJ mix, so that exciting, energetic, tense and relaxing music follow each other in just the right order and at the right time.

Finally, when the DJ knows what songs to play (tracklisting) and when to play them (cue points), he can start mixing the songs together. He starts by playing the first song, and then he’ll play the second song in the background at the right moment (i.e. starting at the cue point). He can prelisten to the second song through his headset without the audience hearing it yet through the main speakers. The DJ then beatmatches the songs by adjusting the second song its timing, and by adjusting the tempo of the second song so that it is equal to that of the first song. Adjusting the tempo happens by time stretching it, where the playback speed of the song is changed without altering its pitch (so without introducing the “chipmunk” effect). When the songs are beatmatched, the DJ transitions from the first song to the second in a process called crossfading. A very simple way to create a crossfade is just decreasing the volume of the first song, i.e. the fade out, while increasing the volume of the second song, i.e. the fade in. However, a good DJ often creates more advanced crossfades by applying equalization filters to the songs, with which he can filter out (what’s in a name, right?) certain components of the individual songs. Most DJing equipment features three such filters per audio channel (per song): one for the bass (low frequency regions), one for the treble (high frequency regions), and one for the mid (the middle frequency regions)3. This allows the DJ to play multiple songs simultaneously during an extended period of time, and at the same time ensure that the songs don’t clash in the bass, mid or treble regions, maintaining a clean sound of the resulting audio.

To create an automatic DJ system, it is therefore necessary to automate all the tasks that were described above:

- Track selection and track listing,

- Analyzing the hierarchical structure of the music,

- Find the beat (and downbeat, see below) positions for beatmatching,

- Find the higher-level structural boundaries for cue point selection,

- Time stretching,

- Beat matching,

- Filtering and crossfading.

Before we’ll go into these topics though, let’s first take a look at why I designed this system for a specific music genre: drum and bass.

Introduction: Drum and bass

The prototype has been designed for drum and bass (DnB) music only, i.e. a particular sub-genre of electronic dance music (EDM). The main reason for creating a genre-specific DJ system is that this allows to make stronger assumptions about various musical properties, which makes many techniques simpler and more powerful and hence leads to better results. Most music information retrieval (MIR) techniques typically try to tackle a wide variety of genres, but this is very challenging, and in some cases a genre-specific approach might be justified, such as an auto-DJ application that requires very precise and robust techniques. The genre-specific approach has been advocated by other researchers as well. Additionally, different sub-genres of EDM typically require different mixing styles: a high-tempo, energetic genre like drum and bass allows for a quicker succession of songs, shorter transitions and playing multiple songs at once, whereas in other genres the emphasis might be on creating longer and more gradual crossfades. In other words, even if it were possible to create a sufficiently accurate annotation system for multiple genres, it would require a tremendous effort to build a DJ system that goes beyond very standard mixing techniques that sound OK for any kind of music, and that adapts to the various mixing styles used for different EDM genres.

If you’ve never heard drum and bass before, or if you’re looking for some examples of good DJ mixes within this genre: have a listen to the BBC Radio 1 Essential Mix by Netsky, the BBC Radio 1 Essential Mix by Camo & Krooked, or some of these mixes (FABRICLIVE Promo Mix collection - over 100 drum and bass mixes!). Enjoy :)

Discovering the musical structure

The first step of the DJ system is to discover the hierarchical structure of the music. A quick introduction to some music theory concepts: at the lowest level, music consists of individual musical events or notes. The melodies and rhythmic patterns, created by the notes, repeat periodically, and this periodicity defines the tempo of the music. This tempo is typically most prominently established by the structured and consistent repetition of more accentuated musical events, typically percussive in nature, creating the beats. The beat is the rhythm listeners would tap along with when listening to the music. In drum and bass, like in most types of EDM, beats can be grouped into groups of four, which are called measures or bars. The first beat of a measure is called the downbeat and it is typically more emphasized than the other beats in the measure; this periodicity of stressed beats (the downbeats) and unstressed beats gives rise to a steady rhythm in the music. Measures are then the basic building blocks of longer musical structures such as phrases, which then make up the larger sections that determine the compositional layout of the song.

The approach the auto-DJ follows to extract this information from the raw audio signal is a bottom-up approach: first, the beat positions are discovered, then the downbeats, and finally the high-level hierarchical boundaries.

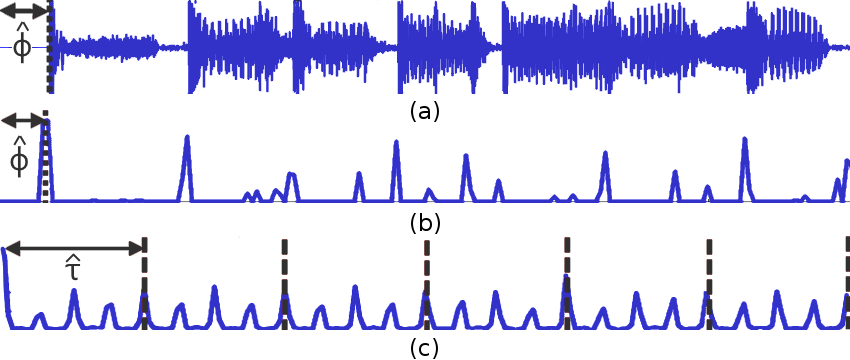

Beat tracking: the first step is to discover the beat positions. This is a task known in literature as beat tracking. The approach used in the auto-DJ system is based on the algorithm by Davies and Plumbley. The basic idea is that the audio is first split up into very short, overlapping windows (of a few tens of milliseconds long). Then, the properties of successive windows are quantitatively compared to each other by calculating their difference: if two successive windows sound very dissimilar, then this leads to a high difference value, else the difference is low. Plotting the differences of all successive windows gives a so-called onset detection curve: this curve approximately detects the positions of musical events or onsets (e.g. playing a note on a piano, or a percussive event), as these onsets lead to a sudden change in the audio and hence large differences between successive audio segments. By calculating the autocorrelation of that curve, the repetitive nature of the music can be analyzed, and this allows to find the tempo of the music (by assuming the tempo is constant throughout the song). Once the tempo (=beat periodicity) is known, only the exact position or phase of the beats needs to be found. This is done by finding the beat positions that align with the highest values in the onset detection curve. The current implementation correctly detects the beat positions of 98.2% of 220 tested drum and bass songs. The figure below illustrates the beat tracking algorithm:

Downbeat tracking: When beatmatching, it is not only important make sure that the beats align when mixing two songs, but actually to align the downbeats. Otherwise, it will sound like the music has skipped a beat, making the resulting mix less coherent. Downbeats can be distinguished from non-downbeats since they are more emphasized. However, this can be very subtle difference, and it is difficult to manually write an algorithm that can reliably detect downbeats. Hence, a machine learning approach is used by the auto-DJ that learns by example to distinguish normal beats from downbeats. The audio is first segmented in beat-long segments, using the beat annotations from the beat tracking step. Various features related to the energy spectrum and onset detection functions are extracted from these segments, using which the beats are individually classified as being either the first, second, third or fourth beat in its measure. Finally, the algorithm selects the downbeat positions on which most individual predictions agree as being the correct downbeats (for example, the algorithm might individually classify some beats as “1>2>4>4>1>2>3>4>…”. It then knows that the first beat is the downbeat, and that it made one mistake: the third beat should actually be labeled 3). This algorithm correctly detects the downbeats of 98.1% of the 220 tested songs. I believe that such a high accuracy can be attributed to the fact that the machine learning classifier learns to exploit genre-specific properties; testing the classifier on other sub-genres of EDM leads to significantly worse results, indicating that the characteristics that describe downbeats in drum and bass do not always generalize to other genres.

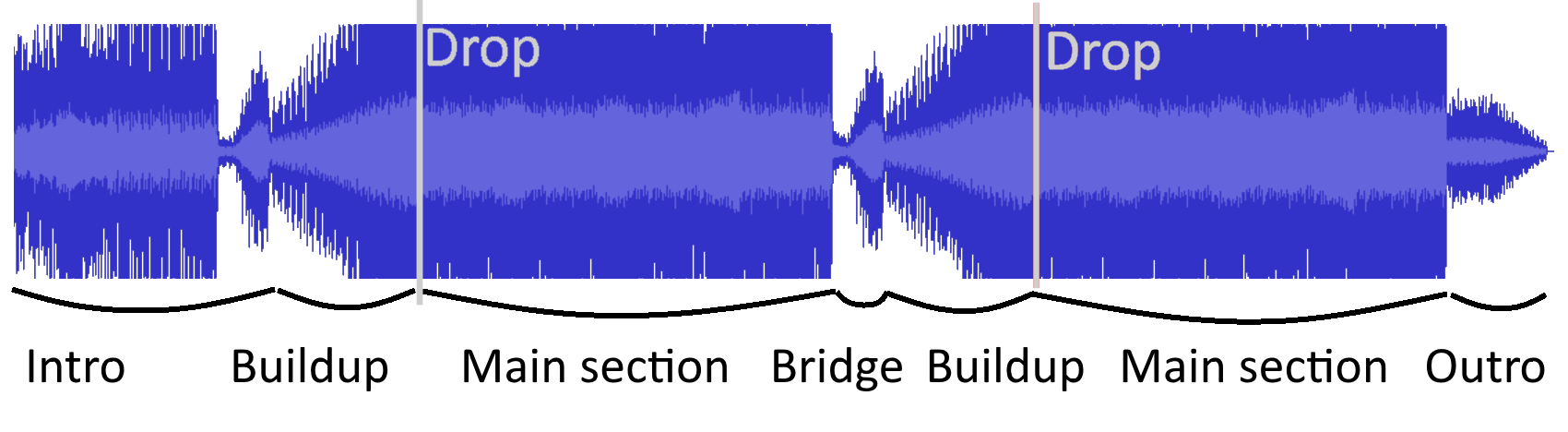

Structural segmentation is the task of finding high-level hierarchical boundaries in the music. In pop music, an example of such a boundary would be the transition from a verse to the chorus. Drum and bass is very different from pop music, but the structural elements that typically reoccur in it are illustrated in this figure4:

This example starts with an intro, followed by a build-up that gradually increases the musical tension. This tension is released in a climactic moment called the drop, which is the beginning of the main section of the music, comparable to the chorus in pop music. The concept of the drop is quite important in drum and bass (and EDM) DJing, and DJs often mix around the drops of the songs to make sure these climactic events occur at just the right time in the DJ set. After the main section, there is a musical bridge or breakdown, that connects the first main section and the second build-up, drop and main section. An outro gradually brings the music to a close. DJs join songs together in such a way that also their structural components tie together nicely. Hence, these structural boundaries play an important role for cue point selection.

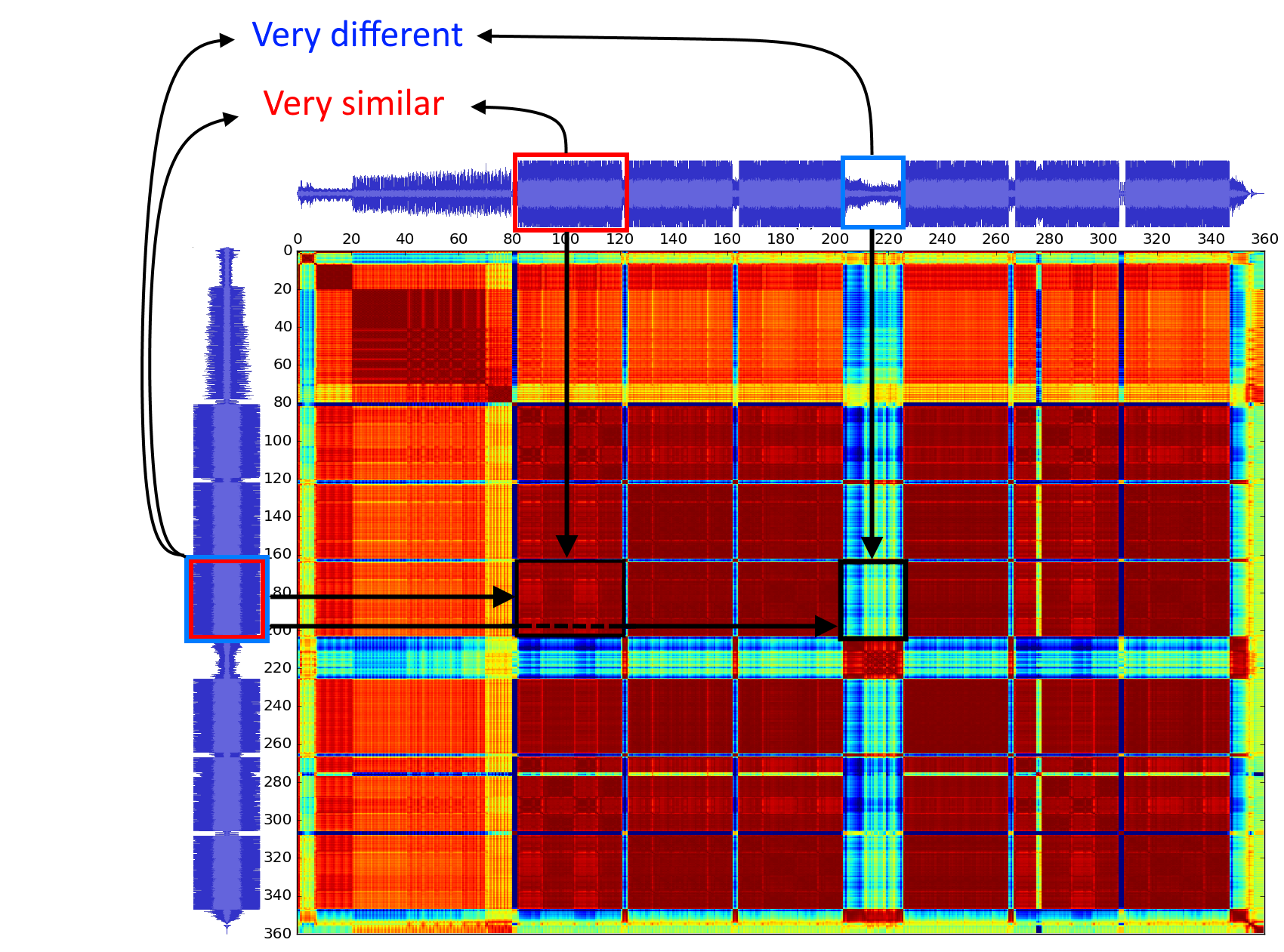

Without going into too much detail, finding the boundaries between these musical segments involves detecting two consecutive parts in the music that are quite uniform in musical properties internally, but that differ significantly from each other. This can be done using a so-called self similarity matrix, which visualizes which parts of the music sound alike, and which parts are different. An example of a self-similarity matrix, with red colors indicate very similar parts of the music, and blue very dissimilar parts (for this song):

The automatic DJ system uses the algorithm by Foote to extract a rough estimate of the boundary locations from the self-similarity matrix, and it applies several post-processing steps to ensure that they are correct according to certain musical rules (for example, structural boundaries should always coincide with downbeats, and are always separated by a multiple number of phrases: a segment never starts in the middle of a phrase). More details can be found in the paper. This algorithm accurately detects structural boundaries in 94.3% of the tested songs. Combined with the 98.2% and 98.1% accuracy of the beat and downbeat tracking respectively, this means that about 90% of all songs are annotated correctly by the DJ system.

Composing a DJ mix

After analyzing the musical structure, the DJ needs to do a few more things to create a mix: he needs to select which songs to play, he needs to select cue points in those songs, and he obviously needs to play the songs and establish the transitions at the right time and with the right crossfading techniques.

Selecting songs

A DJ composes his mix with great care, taking into account various properties of the music. In the auto-DJ prototype, also various musical features are considered: the musical key, the song its “theme” or “atmosphere”, rhythmic patterns and vocal activity.

Firstly, the auto-DJ ensures that the mixed songs are in key. The key of a song is a concept from music theory that defines what notes and chords are used to compose a song. Mixing in key or harmonic mixing then refers to the best practice in DJing where DJs only play songs together if their musical keys are either the same or related to each other. This is important as mixing songs in non-related keys often leads to harmonic dissonance in the resulting mix. The auto-DJ also implements a pitch-shifting algorithm that can alter the musical key of the audio without changing its playback speed, allowing it to slightly change the key of a song and hence increase the number of possible song combinations.

Secondly, the automatic DJ selects songs so that they are alike in “style”, “theme” or “atmosphere”, i.e. the general mood and energy level of the song. For example, a song might be energetic or calm in nature, uplifting or moody, happy or dark and so on. The auto-DJ uses a custom theme descriptor feature that tries to capture exactly these properties. To calculate this feature, it basically extracts some information about the energy and spectral content of the audio and summarizes that into a three-dimensional vector. Given the currently playing song, the auto-DJ selects the next song so that its theme descriptor feature is not too different. It also tries to create a certain progression of atmosphere throughout the mix: for example, if at a certain point, the DJ is first playing a calmer song and after that a slightly more energetic song, then it tries to select a third song which is even more energetic than the second. This effectively creates a build-up of energy over multiple songs. Such a progression mimics the behaviour of human DJs, who usually compose a mix using a progression of energetic peaks and calmer troughs. More details on the theme descriptor feature and the theme progression algorithm in the paper.

The full song selection algorithm works as follows. Using the key and theme of each song, the auto-DJ first filters the music library and extracts the most likely candidates for the next song, given the current song: the songs that are in key and that are most similar in theme to the current song are kept. The next song is selected from this pool of candidate songs based on rhythmic similarity, i.e. the candidate that has the most similar rhythmic patterns to the current song is selected. This similarity is measured by comparing the songs’ onset detection curves (which were also used for beat tracking). However, the auto-DJ also measures vocal activity using a machine learning algorithm, and it avoids overlapping vocal regions during the crossfade as this can be quite a disruptive experience. In the end, (successive) songs are selected so that they are 1. in key, 2. thematically and 3. rhythmically similar to each other, and 4. without vocal clashes during the crossfade.

Selecting cue points

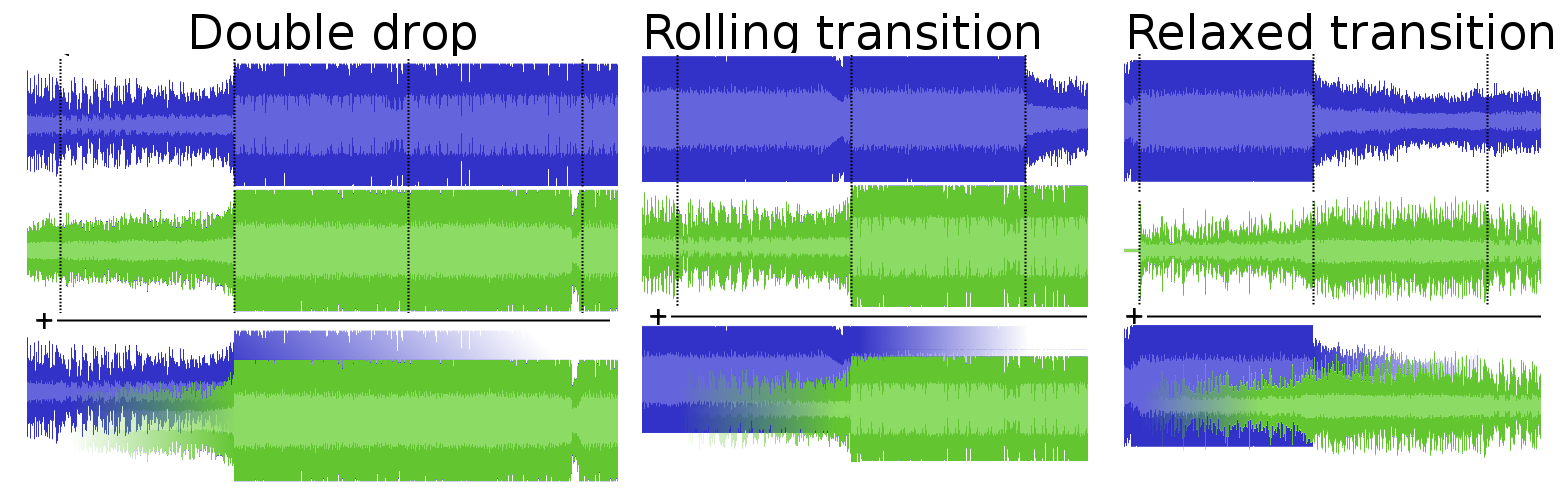

As mentioned before, DJs choose their cue points so that in their mix, important structural boundaries align with each other, or in other words so that a structural component (e.g. the breakdown or outro) of a song seamlessly transitions into a structural component (e.g. the intro) of the next. Many types of transitions are possible, depending on what types of musical sections the DJ wants to mix. The automatic DJ distinguishes two types of segments (“high energy” and “low energy”), and implements three transition types5, as shown in this figure:

- Double drop: Double dropping is a technique that is often used in drum and bass DJing. As the name implies, in this type of transition, the drops of two songs are aligned in time: this obviously leads to a very energetic and climactic moment in the mix. An example (a double drop of Mefjus - Far Too Close and Phace & Misanthrop - Stagger):

- Rolling transition: In a rolling transition, the auto-DJ transitions from the main section of a song into the drop and main section of the next. The second song hence continues the energetic nature of the main section of the first song, which keeps the mix “rolling”. An example (Hybrid Minds - Lost transitions into Hybrid Minds - Meant To Be)

- Relaxed transition: In a relaxed transition, the auto-DJ transitions from a “low-energy” section (e.g. the outro or breakdown) into another “low-energy” section of the second song (e.g. the intro). This interrupts the energetic nature of the mix and introduces a calmer moment, giving the listener some time to relax. Example: (relaxed transition from S.P.Y.-Step And Flow into Noisia & TeeBee - Moon Palace):

Creating a crossfade

At this point, the auto-DJ has selected the songs it wants to play, the order to play them in, and the appropriate cue points. Time to start mixing! When a human DJ creates a transition, he waits until the first song reaches the appropriate cue point, and then starts playing the next song in the background while pre-listening to it through his headset. He’ll adjust the tempo and timing of the second song to ensure proper beatmatching, and after that he gradually fades in the new song while also adjusting the equalization filters to create a clean sound in the resulting mix. In other words: during a crossfade, a human DJ needs to do quite a lot “live”, at exactly the same time as the transition is happening.

The auto-DJ performs the same steps (beat matching, time stretching, crossfading and applying filters), but the difference is that this does not happen at exactly the same time as the transition, but slightly in advance in a background process. As soon as the auto-DJ has determined the next song to play, its cue points and the transition type, it creates the crossfade in the background, while the mix is still playing one of the previous songs. It then stores the generated crossfade in a buffer, and plays it once the audio playback arrives at the proper moment. Beatmatching for the auto-DJ is just cutting and pasting audio fragments at the right instants, given the cue points and beat positions. Filters are applied to the segments cut from both mixed songs, and then the filtered audio fragments are mixed together by quite literally adding (summing) the audio waveforms together. In the current prototype, the transition lengths and volume/filter progression are fixed and depend only on the type of transition.

So.. what’s next?

In summary, the automatic DJ system I developed in the last year can accurately detect the beats, downbeats and structural boundaries in drum and bass music (90% of drum and bass songs receive correct annotations), and it uses this information to create an enjoyable, seamless mix. It furthermore takes most important DJing best practices into account (e.g. harmonic mixing, proper structural cue point selection, theme similarity and flow throughout the mix, different transition types, …). In the end, I am very pleased with this result, and in my opinion this first prototype already delivers quite impressive results.

However, there are still many things which could be improved:

- Currently, the volume fading and equalization filter progression during the crossfade follows a fixed pattern which only depends on the transition type. It would be interesting to let the auto-DJ adapt the filter settings, transition length etc. depending on the songs that are played in order to truly optimize the transition.

- The song selection method already delivers quite good results and a nice, musically coherent mix. However, there are many professional DJ mixes available on the internet: it would be very interesting to see if the song progression and mix composition could also be learned from these mixes using machine learning or deep learning.

- The annotation methods could be improved by adding reliability measures: if the system is too uncertain about the annotations for a song (e.g. the beat positions), it could ask the user for manual corrections, and exclude the song from the mix to avoid making mistakes.

- Extending the system to more music genres would also be interesting. However, the current system works this well because it is constrained to one genre only, so extending it would probably require to finetune the used techniques to the new genres and building some sort of genre recognition system (or use the exact same algorithms for all genres, but I believe this might not work as well as this ignores genre-specific properties). Additionally, this would require figuring out how to nicely transition between different genres, when to do that, and how to translate that into an algorithm.

- The prototype isn’t too visually pleasing or user-friendly as it is a command line application. It also only works on Ubuntu 16.04 for now6. Creating a nice GUI and porting it to other OS’s would be a nice addition.

The code for the prototype developed for my master’s thesis can be found here. I have extended this prototype for my paper though, and the link to that repository will be announced later once the paper has been published. Stay tuned!

Footnotes

-

Len Vande Veire, “From raw audio to a seamless mix: an Artificial Intelligence approach to creating an automated DJ system.”, Ghent University (2017). Promotor: Tijl De Bie. ↩

-

Currently under review, link TBA. Stay tuned! ↩

-

The low and high filters are typically shelving filters, while the mid filter usually is a peaking filter [source]. The manual of the Pioneer DJM-800 specifies the low filter shelving frequency at 70 Hz, the mid filter center frequency at 1 kHz and the high filter shelving frequency at 13 kHz. Most DJ equipment also implements low- and high pass sweeping filters, but these are not implemented in the auto-DJ system (yet). ↩

-

The high-level musical structure shown here is by no means strictly defined, and I found that there even isn’t a common terminology to refer to the different parts of this structure (e.g. the “main section” or “bridge” might be called differently by others). ↩

-

Note that these transition types are mere abstractions of common transition styles, but in reality these are of course not very strictly defined (nor are the names used for them in this blog commonly used - apart from the term “double drop”). Of course, other types of transitions are possible as well. ↩

-

It might work on other OS’s if you get the dependencies installed, but no guarantees there… ↩